Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

A roadmap to lands real and fictional.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

In this chapter I will present the reader with a number of ways we can approach the concept of the author, and how to critically deconstruct and analyze it. All the methods I mention here are viable and used in media and art analysis. I will present the various methods in a rough historical order.

Note that, just as my other texts in this series, this chapter is simply meant as an introduction to the topic, and a way to start learning more about the media we all love to enjoy.

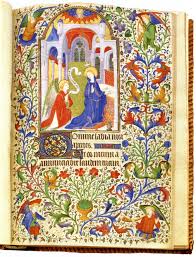

Without going too far back, but still getting some context to the rest of the text, I will start by quickly describing how scribes worked in medieval Europe and how these scribes created their codexes, texts created to be specifically made for a single customer’s needs. A scribe was foten, but not always employed by a monestary, and were tasked to copy texts for reditrtbuition and selling. Some texts were copied as is, but many texts were made out of materials from various diferent texts, to create compilations of certain topics.

These compilations of knowledge could contain anything from poetry, to history and philosophy and alchemy. It was not uncommon for historical or mythical events to be subtly changed to give the contractor’s family a bigger role in the commissioned version.(Woodmansee, 1994). More importantly were these books seen as objects in and of themselves Many of these texts that were sold, were carefully and lovingly edited and decorated by the scribe or one of the scribes colleagues. These codexes as a result were created as unique one of a kind items. These items were created in a communal setting, with a clear tradition and history behind their creation (Barthes, 1968).

There were of course well known named authors and scholars in medieval and renaissance Europe, though much less before the introduction to the printed word. These writers would publish under their own name, and have their works copied and circulated by the above mentioned scribes. Attributing one’s findings and research to a more well known, or even mythical figure was also far from unheard of either

I bring this up primarily as a background for what we will discuss later on in the chapter, that what we imagine as the writer and the artist is a relatively new invention all things considered. What is of most import to this discussion is the fact that the author, creator of the text, and the text itself was not nearly as closely entwined as they are today.

During the late medieval and renaissance period, a new image of the creator and artist started to arise. The individual changed from a craftsperson that has worked within a tradition of art and craftsmanship to create singulair items, into a genius creaing series of texts or works. This new creative figure worked in isolation, and whatever they created, was from their own mind, or divine inspiration. This is in stark contrast to the more collectively driven bardic and craftsman traditions of past artistic endeavors (Barthes, 1968).

Ownership of the art also moved from the owner of the piece, to the originator of said piece. This has a number of reasons, as well as ramifications, but we are interested in two of these today, intellectual property rights, and canon forming (Barthes, 1968).

By strengthening the image of the writer as a genius, of one with almost divine inspiration, could works be more tightly tied to them. This meant that a specific work of art was seen as the unique and singulair creation of the genius artist, rather then the continuation of a comunal tradition. By tying the work to a singular person, can more strict control over production and distribution be justified (Barthes, 1968, Woodmansee, 1994). The elevation of the creator of art, from a mere craftsperson to one of an artist and genius also helped funding in a landscape where patronage from wealthy nobles and business men became less and less available.

We would today argue that no creator exists in a vacuum, and this approach aims at understanding the text and the creator from their contemporary history. Every written word can, acording to this methond be placed within a certain context, that can, at least partly explain why the work turned out the way it did. J.R.R Tolkien’s works can for example be contextualized by his dramatic experiences fighting in world war 1, where he got a first hand experience of the brutal war machine.

We must always be weary in that when making these sorts of analyses we can not fully escape our own biases. Our knowledge and lived experiences will inevitably lead us to focus on certain aspects of the author’s experiences over others. With that said, a thorough investigation, and immersion into the context of a work’s creation, can open up a more rich and detailed understanding of the text you are taking in.

The phrase “Death of the author” refers to an essay by French literary scientist Roland Barthes (1915 – 1980) by the same name . This essay formed the basis of a new form of analysis that discards the agency and creative power of the writer, in order to move the text to the forefront of the analysis. The arguments layed forward, and that are often used in modern literary criticism can be laid out like this. The authorial intent of a text can take two forms. They can either:

a) Be apparent in the text, and as a result, it would be pointless to ask the author, since the reader can discern it themselves.

b) Not apparent in the text, and as a result, was the author unable to bring forth their intention, and as a result, it is not relevant to the text.

This removes the focus of analysation and interpretation from the author, and moves it to the reader themselves. No longer would the writer have the utmost say in what and how their works conveyed (Barthes, 1968. Woodmansee, 1994). These ideas tie closely into the idea of sender-message-receiver I discussed in the previous chapter.

To give a practical example. Will Wright, the creator of the series of video games, the Sims has argued that he did not create the game The Sims 1 in order to parody the modern American dream. I would argue, and many others have, that this is just what Will Wright did. I would argue that the focus on the acquisition of material things, chasing careers, and eventually owning the biggest house on the block, neatly transfers into a cynical, if lighthearted take on the capitalist American dream.

This method does have several advantages, primarily by removing anything between you as a reader, and the text itself, at least for as far as that is possible. I want to once again reiterate that allowing yourself to take the author, and their lived experiences into account, will also equally lead to interesting discoveries about the text in question.

I have with this chapter presented a few ways one may look at the concept of the author and how we might understand them in relation to their work. The author has in this text gone from being a craftsperson or the creation of a text, to isolated genius, to being a genius that wads non the less influenced to their environment, to once again stepping down and giving the text the ultimate center stage.

All these methods do have their uses, and I wish that my readers will see these, not as competing theories, but rather as tools that can be applied to different problems when it comes to thinking about art and media. In the next chapter we will add even more tools to this theoretical toolbox.

Sources and further reading

Barthes, R. The Death of the Author 1968 – University Handout

Woodmansee, M. (1994). The author, Art, and the market: Rereading the history of aesthetics. Columbia University Press.

The concept of the professional writer has changed wildly over the years, and are indeed still changing to this day. What this texts is going to focus on specificity is the invention of the printing press in Europe, and what that meant for the world of the written word, both socially, cultural and economically.

The ideal text is a concept within many fields of research, and has number of different connotations. In this text we are interested in the concept in therms of literary and writing history. The concept of the ideal text in this context is a text that is as close to the authors original intent or “original text”. In order to create these ideal texts are usually many different translations and editions used, to see which parts and passages that seems to correlate the best with each other. From these different editions is a so called Ideal text created. This text would then work as a basis, or a reference point for further studies.

One good example of such an ideal text would be certain plays made by Shakespeare, of which we only have second hand notes and recordings off. Plays being a personal property of the theatre troupe, and never shared outside the company, was the only way to acquire other theatres plays, to sit in the audience and try to record it line for line.

To understand the cultures of the medieval scribe work, and how the printing press changed it, one must first understand the concept of the Manuscript. The Manuscript of the medieval European scribes, and their coupes across the world is in and of themselves unique items. Each and every one of them created by a person, at a specific point in time. Things like spelling and grammar errors, translations errors, as well as corrections to these errors, al leads to the further differentiation of a text. Furthermore were many scribes not just tasked with creating an item of functionality, but also of creating an articulacy of value and beauty.

One of the results of this is the fact that we need to conciser that, unlike a published and printed book, was these manuscripts made for a specific individual, or a small collection of individuals rather then for a public.

Many manuscripts were made for specific nobility or other inportant individuals, and it was not uncommon for historical or religious texts to be custom tailored to collaborate the stories and features of the ancestors of the chosen patron. These texts were, and still are considered great works of art for a very good reason, as many features large masterfully made artworks, as well as pretentious and rare materials, such as gold and rare pigments.

The image most have of the medieval scribe is of an elderly monk sitting hunches over his text books and slowly tracing the words and images of his predecessors. The work of the medieval scribe was indeed a lot mover involved then that, and often included correcting spelling errors or factual problems that the author has left in, (and accordantly creating their own errors from time to time). The work for the scribe was often seen to be of just as an inportant and vital task as the original author, and the two were seen as co creators for each work. It was indeed a common practice for the scribe to make themselves a small portrait in the manuscripts themselves.

The creation of each and every manuscript was as a result a unique and one of a time production, and each object that was created in this was was as well, a unique artefact. This will be put in to contrast of the mass produced series of identical texts possible with the invention of the printing press.

The concept of copy rite and ownership relay came to a head when the printing press and its use became more and more widespread. It became more and more easy to copy, redistribute and acquire the written word. This did do a lot of good for he spread of art, culture and science, as well as differing political ideals. One group that was both gained from, and suffers at the hands of the printing press was the authors of these new texts.

The authors of the renaissance had a vast new audience of hungry readers, but no clear way of safety monetizing said market. It was not uncommon to acquire books form other printers, and then undersell them by producing cheaper copies. These infringements was mostly done over national borders, and a few duchies of the holy Roman empire was nutritious for these bootlegging printers. They acquired books form across the border, and then managed to make significantly cheaper copies, due to them not needing to pay the original author.

The difficulty of the author, and publishers to properly monetize their products lead to the invention of more clear and universal copy write law. In order to properly push their newfound claims. To be able to properly make these claims, a new image of the author had to be created.

The idea of the author of a author as a a unique genius, that springs original concepts from their very essence is a relatively new one as well, one which origin can be argued to be traced to (at least in Europe) the invention and refinement of the printing press.

In order to protect the writers livelihood in this new environment, was an image of the proses of writing, and the author was needed. German authors in particular was hurt by the introduction of the printing press, and its consequences for their ability to protect their economic safety. The concepts of a writer living solely on sales of reprints of their books are a relatively new concept in Europe. Before was writers usually paid on commissions, or even more often, by patronage of a noble or other rich individual. This new writers found themselves completely without any sort of safety net. In order to make sure these writers could protect their income and works, would they need to reinvent the very role of the author (Woodsmansee 1994). I will here present two different definitions of the author, and how it relates to the medieval manuscript.

The renaissance, and pre printing press idea of the writer, was mainly that of a craftsman. An individual that has learned a trade, and applies heir tools, experience and the knowlage of previous craftsmen to create new works out of existing myths, stories and narratives. Much like a carpenter works with already existing wood, so does the writer work with pre existing themes and ideas. (Woodsmansee 1994)

When a writer seemingly created a completely new topic or concept, this was not attributed to the individual themself, but rather to some sort of divine or supernaturally inspirational force, be it a deity or a creatures such as a muse. Note that this puts the professional writer, in the position of a vessel for other ideas and beings, rather then being the originator of said ideas themselves. (Woodsmansee 1994)

After the introduction of the printing press, and the coming of the enlightenment, did another concept of the writer, the artist. This individual worked towards unevenness and individuality, they were the sole source of their work, and as a result the sole owner of it as well. Their inspiration came from within, lacking any mundane or supernatural force of inspiration. Because the writer is the single originator of the text, they also held the single credit and responsibility for the text, and as a result, also the single monetary and intellectual rights to it. (Woodsmansee 1994)

The influences of craftsmanship also disappeared gradually, and was instead replaced by the concept of solitary artistry. A similar trend could be found in al of the disciplines that would later be known as the “fine arts”. These being dance, theatre, paining, sculpting and writing. In al these disciple was there a clear move made to make a distinction between the crafts and the arts, as well as elevating the later over the former.

What I have tried to present here is a n introduction is a shift in mentality and reality of both the author and the book as an item when the printing press was fully introduced in Europe. With the artefact created going from a physical unique item, to the ethereal idea of the Text, so did the image of the writer go from the craftsman scribe, to the artist writer.

P.F.F. (2006). Manuscript, not Print: Scribal Culture in the Edo Period. The Journal of Japanese Studies 32(1), 23-52. doi:10.1353/jjs.2006.0016.

Woodmansee, Martha (1994). The author, art, and the market: rereading the history of aesthetics. New York: Columbia University Press

This chapter will be the first in a series of texts commissioned by the followers of my twitch channel (link in the references). To get your own chapter dedicated to a topic of your choice (within reason), go to my twitch and collect 8,000 channel loyalty points by watching my stream.

This chapter will be dedicated to the depiction and use of food within the context of both real and fantasy foods in a roughly medieval European setting. We will tackle this topic form two angles, the first will present food in a medieval historical, cultural and medical context. Our second context will be that of a narrative tool, more specificity to look at how fantasy literature uses food in order to describe build and contextualize their worlds.

We will star this chapter by examining the concept of medieval food form a series of different angles. Food is closely linked to the social and economical situation of the individuals that prepares and consumes it. (Towle, et al 2017)

The food of medieval Europe was closely tied to health and having a healthy life. The most prevalent theory of medicine at the time consisted of Hippocratic School of medicine, or the theory of the four humours. The idea that the body have four essential liquids, which is in turn tied to one of the four elements of western alchemy.

In order to keep a healthy body, one must make sure that their humours are properly balanced. One of the easiest, and most practical was to balance once humours was simply to eat a diet that contains al the needed humours. If one for example needed to have more phlegm, which is tied to water, one need to consume something related to waters two properties (wet and cold). One things that would work for this would be fish, as it comes from water (wet and cold), and as a result, has some of the elements of water, and as a result, the properties of phlegm.

Bread and porridge seems to have been a common staple of most British individuals living in the Medieval ages, regardless of social class. As noted before what the lower classes forced to sustain themselves on whichever foods that were the most readily available to them, so fish for example was mostly consumed near bodies of water where edible fish where found. This means that they were not able to follow the rules ranging the four humours as closely as those of higher social and economical classes.

The study performed by Leschziner et al (2011), seems to indicate that the medieval cooking more wildly combined different flavours throughout the meal. For example was sweet flavours not simply used as an end to the meal, but used equally as much as the other tastes. This was done party because the way meals were first and foremost created to make sure that the meal contained al the four elements needed to keep a harmonious balance of the four humours. Sugar is also believed to have been seen as another spice, and was as a result used as one. Sugar was also used as a preservative at the time. Medieval Europe also saw the split of pickling from other general cooking Leschziner (2011).

As I have hinted at was, and is food very much tied to your class and status within a given community. What you ate was, even more then today tied to where and how you lived. Some studies, for example the study by Towle et al (2017), shows that the diets of many city dwellers were indeed rather diverse, and contained a lot of fruits and greens. Individuals in rural areas were mostly limited to eating whichever foods were produced and sold nearby, so seafood and fish was usually eaten amongst the coast or other bodies of water for example.

There is no secret that many fantasy books are filled with talk of food. The sheer number of cookbooks, both official and unofficial attests to just how big of a part food plays in many fantasy narratives.

Food used as a narrative device is by no means limited to fantasy narratives. A commonly brought up example is the Oranges in the Godfather. Every individual handed an orange in the film, is killed shortly after. In fantasy narratives on the other hand are food often used to create a sense of the world and how it functions. These is especially true in fantasy, where a lot of the setting is needed to be described and contextualized for the reader in order for them to understand the stakes and themes of the narrative. Food is an excellent way to tie the world in to a larger context, as well as to use it as a shorthand to compare it to other real life settings. The heathy and rural food of the Hobbits in the Lord of the rings series, draws clear ties to the English countryside. By introducing the eating habits of the Hobbits as comparable to that of the British countryside, especially during the 18th centenary, does the writer go a long way to tie the entire region and people of the hobbits to the British countryside as well, (if a rather picturesque and idyllic version of it).

Food can be used to explain how certain aspect of the world works. An easy example would be the Lembas bread. These magical breads are able to sustain oneself for weeks. This dry bread can keep an individual not only alive, but also healthy for long periods of time. Food, especially in relation to magical and mystical topics, can help ground otherwise abstract subjects in more mundane terms. The preparation and serving of food (see, the cooking tools, producers and types of storing), can also be a good indicator and pointer on the overall state of technology in the setting of the narrative, as well as the characters relationship to said technology.

As described earlier in the text, is food, especially in medieval settings, very much tied in to the class of the individuals consuming it. The ice and Fire series uses food to a great extent to show the differences between the squallier of the peasantry and the opulence and grandeur that the noble houses live in. Food is also a good indicator of the different cultures and traditions present in the narrative.

The abundance of food in Hogwarts, where Harry feel safe and welcomed is put in to stark contrast to the near starvation he faces at the hands of the oppressive and cruel Dudley’s. The examples of this trope are to numerous to list, but needless to say, there is no accident that food has been used within fiction, fantasy and otherwise, to show the wealth and statue (or lack there of), of characters within fiction.

Food plays a large part of human identity, real as well as fictional. you can learn a lot about a culture from what they do and do not eat. In this text I have tied to show how you can understand both fictional and real cultures partly tough their food. As always are these chapters simply meant as an introduction to these topics, and I have provided a series of further reading in the sources.

JURAJ DOBRILA UNIVERSITY OF PULA DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES SUB DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

https://dcplive.dekalblibrary.org/2011/05/20/food-in-fantasy-literature/ https://www.tor.com/2019/03/14/the-fantastical-food-of-fantasy-fiction/

Dietary and behavioural inferences from dental pathology and non-masticatory wea Towle, Ian & Davenport, Carole & Irish, Joel & De Groote, Isabelle. (2017). Dietary and behavioral inferences from dental pathology and non-masticatory wear on dentitions from a British medieval town. 10.1101/222091.

Leschziner, Vanina & Dakin, Andrew. (2011). Theorizing Cuisine from Medieval to Modern Times: Cognitive Structures, the Biology of Taste, and Culinary Conventions.

My twitch: https://www.twitch.tv/samrandom13

This chapter will tackle one of the more iconic classes of Dungeons and Dragons- the Cleric. In this chapter, we will discuss the more common tropes of the cleric, how it ties to the Catholic faith, as well as other fictional representations of the same archetype. In part 2, we will explore some of the sub-classes of the Cleric and try to find a real life connections of these varied archetypes.

The Cleric is a magic user, healer and warrior. The power of the Cleric comes from their gods rather than inert magical abilities like that of the Sorcerer, or from intense studies of the arcane arts of the Wizard. This difference gives these magical classes considerably different approaches to what magic is and how it is used. (Wizards of the Coast 2019)

The Cleric is described as more than a mere priest or devout follower. These clerics are mortals that are chosen by their deity to receive some of their divine power. The interesting aspect of this is that the Cleric can as a result lose his power if they anger their patron god, or lose their good graces. (Wizards of the Coast 2019)

The Cleric of D&D is not, as we will see, tied to any one particular faith or creed. The Cleric is very much the catch-all term for individuals that have in one way or another, gained divine powers from a greater godly power 1. These would, in terms of Medieval Europe, might be a parallel to a prophet, soothsayer or other even a saint2.

The Catholic church is what comes to mind when Clerics are discussed within a western context4. The Cleric, in the context of the Catholic church, usually refers to the priestly office in some capacity. These clerics had a large authority over medieval society, both within and outside of theological matters. These powers came partly from their monopoly of the language of the Holy book5, which was Latin. (Wilson 2018)

When discussing this instance of the Clerical archetype, I will refer to the medieval Catholic Cleric, and his office. It is hard to overstate the importance of these men within the social order of Medieval Europe, for good and for ill. Faith, as in many different places around the world, was both uniting and dividing force. An important factor to keep in mind is that the Medieval Catholic clergy, as well as the clergy of most major religions were part of the privileged part of society. (Wilson 2018)

In his book A magical world: superstition and science from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment does Wilson (2018) describe the Miracle as the “bread and butter” of the Catholic church. The saints and the miracles they produce are meant to lend legitimacy to the church, as well as be the basis for the divine powers of the prayer. By praying at certain places, in certain ways, a devoted follower would be able to gain certain blessings. (Wilson 2018)

Miracles are of course a major part of other religions, as are prayers, but I believe that the original inspiration from Wizards of the Coast primarily came from Catholic Christianity6. With that said, D&D as time went on, has added more and more influences as the franchises. As a result, their player base grew. We will take a look at this wider source of inspiration and world-views.

The prayer in Dungeons and Dragons, when performed by a Cleric, follows the same general theory. The Clerics prayer is most often directly answered in some way by their deity, in form of a spell, blessing or curse. Purely mechanically speaking, this is similar to a Wizard casting a spell. (Wizards of the Coast 2019)

The most striking image of the Medieval Catholic priest is that of a stoic man in long flowing robes, carrying books, scrolls or incense. These articles are vital to the performance of the office of the Cleric or priests. These objects are often referred to as symbols of office and serve as a unifying force for the faith in question. The symbols of office also allows the priests to give their prayers a lot more weight and importance than they would have if anyone else performed them. (Bourdieu 1991)

This image of the robed holy figure is one that we can easily find in Dungeons and Dragons, as well as other contemporary fantasy works that take place in a similar time period. Below we have two images, a Cleric from the 5th edition Dungeons and Dragons and a Priest from the MMORPG7 World of Warcraft. Here we can see clear connections between the visual aesthetics of the Medieval Catholic church and these two gaming narratives.

The office of the Cleric, is in gameplay, the focus of their divine power and the centre point for their magical powers. This is in contrast to the Wizard, who needs to use components, or an arcane focus to cast spells. This magical force, like much in Dungeons and Dragons, is partly left to the discretion of the DM. A number of smaller details are in fact, left rather vague, for the possibility for the DM to modify and better fit their players. The symbol of office, in the case of the Cleric in D&D, is their focus of their power and the tools they use to cast their spells. In other words, the symbolic power of the Catholic cleric becomes a physical tangible power in the case of the D&D Cleric. The symbols of office, or the holy symbol as it is called in game, is vital for the Cleric to perform their magic. These symbols can take many forms- from books, to talismans to swords, but they all have the same function, to let a chosen wielder to be heard by their chosen deity. (Wizards of the coast 2019).

The pantheon of the D&D world is vast and complex, We are going to give a very brief overview here of the various pantheons. The gods for good or ill have a large presence in the world of Dungeons and Dragons. Deities can be contacted both directly by individuals such as clerics, or by prophets via prayers or indirectly through prophecies and signs. The pantheons and gods that are presented in the official D&D materials are way too numerous to go into detail here. We will go through the general outline of how the pantheons work, and how they are organized. (Wizards of the coast. 2019)

The Pantheons of gods we will discuss today are roughly sorted into two categories. The first category goes by the name of Deities of the Forgotten Realms, or the gods created specifically for Dungeons and Dragons. The second category is the so called Fantasy-Historical Pantheons. The Fantasy-Historical Pantheons are all based on real life gods from the Greek, Egyptian, Celtic and Norse faiths. These gods have a clear grounding in real life faiths, and we will go into more detail with them in the next chapter. (Wizards of the coast. 2019)

The gods are further sorted into categories based on their domain of influence as well as their alignment. These alignments inform a lot of how the character in question are predisposed to act. These guidelines help role-play, as well as keeping the characters consistent, between sessions and campaigns. (Wizards of the coast. 2019)

These different gods all have a realm of power or responsibility. Note that these areas often overlap. This makes sense, since not every culture in D&D worship every deity. As with real life pantheons, several gods of life for example exist within the same geographical area. In terms of D&D, we have for example we have the god Ilmater, god of endurance, who is a lawfully good god, with reign over life Life and his symbol is a pair of hands bound at the wrist with red cord. Another god with reign over Life is Chauntea, goddess of agriculture, a neutral good goddess of Life with her symbol being a sheaf of grain or a blooming rose over grain. It is up to the DM to use these gods how they see fit, as well as in which configurations they are used. As I mentioned before, much of D&D meant to be modified and transformed to fit the players and DM the best. (Wizards of the coast. 2019)

We had as a goal in this essay to analyse the connections between the D&D Cleric and their real life counterparts. I believe we have managed to point towards a series of interesting connections between Dungeons and Dragons and real life religious practices, in this case, the Catholic church. Much of the visuals, such as the symbols of office, the clothing, as well as the general mythos of the role is shared by both incarnations. The focus on prayers, as well as miracles and the performance of miraculous things are present in both roles. Lastly, the symbols of office or the holy symbols do carry great weight when it comes to performing these wonders and miracles.

Next chapter will be dedicated to another spellcaster that uses divine or otherworldly powers, the Warlock.

1Note that Clerics are not the only classes that get their powers from a divine source. Some other notable examples are Paladins and Warlocks, which we will discuss in later chapters.

2 All individuals that were believed to be able to perform miracles in one form or another.

3 Not to be confused with the D&D class, the Monk.

4 A context of which Dungeons and Dragons were created (Wizards of the coast).

5 See, The Bible.

6 I base this assumption on the fact that Wizards of the Coast is a primarily American company, that at its conception primarily sold to an American public. As a result, would it make sense to tie the Cleric to a religious context this public would be the most familiar with. (Wizards of the coast)

7 Massive multiplayer online role playing game

References:

Wizards of the coast. (2019). Pantheons. Retrieved 2019.09.25 from https://www.dndbeyond.com/sources/basic-rules/appendix-b-gods-of-the-multiverse

Wizards of the coast. (2019). Cleric. Retrieved 2019.09.25 from https://www.dndbeyond.com/classes/cleric

Wilson, D.K. (2018). A magical world: superstition and science from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. (First Pegasus books hardcover edition.) New York, NY: Pegasus Books, Ltd.

Bourdieu, P. & Thompson, J.B. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Further reading

General texts on the chatolic faith or mission

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04049b.htm

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25133/25133-h/25133-h.htm

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52040/52040-h/52040-h.htm

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/11553/11553-h/11553-h.htm

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/18039/pg18039-images.html

Further reading on symbols of office

https://www.dio.org/bishop/symbols-of-the-bishop.html

The modern myth of the Wizard may be traced back to the renaissance in Europe, but the concept of magic and the men and women that could wield it goes way further back then that.

In this series will we discuss some of the classes available in the Tabletop role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, and put them in a larger fictional and historical context.

The concept of the wise old man with a long beard and a flowing robe is far from a new one, both in fantasy and in general lore as well. The modern idea of the mage can be traced back medieval Europe and the Renaissance as well and the middle ages. This mage or wizard gained his power trough diligent studies and the manipulation of the natural world to his advantage. The mage is seen as a seeker of knowlage and truth, in comparison to the Sorcerer and the superstitious magic user of the countryside. This can very much be understood by the climate of the times and the need to distance themselves from the heretics that the Inquisition were hunting at the time (Levi 2017).

The fifth edition handbook describes the wizard as a scholar of the arcane. Tough his craft does at first seem simple and their powers come form a single utterance of a short word, or waving of the hand, does this hide vast hours of preparation, study and meditation. The idea of the Wizard as a scholar is further cemented in the form of Arcane Traditions, these traditions are described as philosophical schools of thought, or general areas of study. A wizard tends to specialize in one of them. (Wizards of the Coast 2014)

A mage becomes more and more powerful the more he or she studies the magical and natural world, this concept that exists within both sources we have discussed so far. Lévi argues that true magic can only come from study, and the wizard of Dungeons and Dragons must spend several decades of apprenticeship and studies to acquire any form of real power. In other word does their dedication to their studies and search for magical lore leads to the gain of real life wealth and power.

Booth texts puts large emphasis on the fact that the visual aspects of the magic, the hand waving, the chants and the components, are but a small part of the spell. The real power comes from within the mage itself, and from his long and careful preparations.

In Lèvi´s texts (2017), as well as the text of his contemporaries is the Mage presented as the user of light and good magic, in comparison to the evil superstitions of the Sorcerers and Necromancers. This dichotomy between science and superstition, high and low, city and country has been written about in several places. This will not be our focus point today, but non the less will it be consider (Levi 2017). The magic in Dungeons and dragons, are as in many fantasy worlds organized in to good and evil magic to some extent. Dungeons and Dragons most clear example on “evil” magic, would be the study of necromancy (Wizards of the Coast 2014). Lèvi also condones any use of Necromancy in any shape or form.

When most think of the image of a Wizard, they think of an old man in long robes and with a large white beard. Much of this image I would personally like to attribute to Tolkien’s works, but Dungeons and Dragons as well.

Here we have two examples of Wizards as they are presented by Wizards of the coast1. Here we can see a clear symbols of the mage, the staff, the robes and the book/scrolls of his practice, not shown here is the wand, a symbol that is often related to the wizard as well2.

Lèvi discusses a series of artefacts in his text. Chief amongst these are the robes, the staff and the magical wand. Levi explains that these artefacts are al needed to properly control the Astral light. He continues to g in to deep detail about how these instruments should be prepared, used and preserved. The robes in particular corresponds to the certain days of the week, which in turn reoffered to the different celestial bodies. (Levi 2017)

Many of these elements can be seen in the Tarot card The Magician. The Tarot is one of Lévis largest inspirations, and are a large element of occult studies even today. In this card can we find several of the artefacts we have already pointed out. Here we see the robes, the staff and of course the inportant wand. Note that there are several artefacts the Magician carries that do not have a clear translation to the D&D wizard. Chief amongst these are the sword, the talisman and the chalice or cup. Note that Lévi makes account for al of these in his text on occult science.

This is the layer of magical energy that the Wizards of Dungeons and dragons uses to manipulate the world around them. This underlying force that combines everything in the multiverse (Wizards of the Coast 2014). A similar concept can be found in Lévis texts in the form of the Astral light. This once again the unifying force that ties the world together. Levi compares this Astral light to a series of contemporary ideas about magic and divinity, such as animal magnetism (Levi 2017).

Both of our base texts built around the idea of a long historical tradition of study, as well as the idea of lost knowlage. That the forbearers grasped magic to a much higher degree, and that it is up to today’s Mages to find this lost knowlage (Wizards of the Coast 2014). Lévi (2017) in his studies ties a lot of his research back to the Egyptian and Greek knowlage on the arcane and religion. In Dungeons and Dragons is the call of knowlage very much used as a reason for the Wizard to leave their laboratories and workshops and go out in world and explore and discover old secrets of the world. Lévi also attributed much of his research to the Cabala of old, a topic way to big to take up in this text, but one we might return to.

The bread and butter of many magical vocations, including that of Dungeons and Dragons. Lèvi, amongst with his contemporaries all dabble in these arts, as well as the art of Divination. In the Era of the Renaissance and late the enlightenment did many nobles and lords still decide on wars and inportant meetings based on the alignments of the stars. It was the job of the mage to interpret and rely these messages from the stars (Wilson, 2018).

Alchemy was also a well trusted source of knowlage, power and wealth at the time of Lévi and earlier. Many Renaissance scholars and scribes were dabblers in magic as well as natural and social science. Much of was written in these subjects, at least in Europe, was done so with a clear Christian angle and viewpoint. It was hard, if not impossible to separate magic, science and religion.

An interesting side note, the famous Dungeons and Dragons spell Prestidigitation, is a French term, that toughly translates to “slight of hand trick” or “visual magic trick”. An amusing coincidence considering the fact that Lévi and many of his occult contemporaries were indeed from France.

we have in this text endeavoured to tie the Wizard of the Dungeons and Dragons, to his real world counterparts. We have managed to tie the practises, history and visuals of the fictional mage and the Wizard in Dungeons and Dragons.

I argue that we can find several connections between the two images of the Wizard archetype. I would not go so far as to draw direct lines between the two, but it does point towards a somewhat unambiguous and universal view of the Wizard in the west. This text also has quite effectively managed to draw links between modern pop culture and the traditions that came before it, our era do not exist in a vacuum. This is one of the major goals with this blog, to show our popular media, in a broader social and historical context.

If you find this topic interesting then I have a few suggestions for further reading in the references, and I will be adding more to this list as I find them. Feel free to share your suggestions and advice for further research in the comments.

References

Agrippa von Nettesheim, H.C. (1986). Three books of occult philosophy … London: Chthonios.

Wizards of the Coast (2014). Dungeons & dragons Player’s handbook. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast LLC.

Lévi, Eliphas (2017) The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic : A New Translation

Wilson, D.K. (2018). A magical world: superstition and science from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. (First Pegasus books hard-cover edition.) New York, NY: Pegasus Books, Ltd.

1The company responsible for the release of Dungeons and Dragons. Note that they to share the name of today’s chapters namesakes.

2An image popularized in to contemporary pop culture much thanks to J.K Rowling Harry Potter series, a series we will in the future discuss in relation to renaissance magic as well.